Seek the Skies

CRITICAL STEWARDSHIP | VOICES

“Stars above that shine and glow

Have their image here below

Flames that from the earth arise

Still aspiring, seek the skies”

Whitin Observatory is a very special place. It stands as a testament to the Wellesley College mission, as a place where women are empowered to make a difference in the world (or better yet, the universe). Since 1900, the observatory housed the Astronomy Department and only in the last decade, it has welcomed new disciplines. It holds a dear place in my heart as the first professional project I saw from start to finish. I recall very vividly my initial visit, when we understood it immediately as beloved and rich with meaning and purpose. The white marble facade, the original wood & brass telescopes and the picturesque perch speak to the importance of the endeavors here. It is a masterful yet humble home for serious research and I only recently truly appreciated the mind and heart responsible for its vision.

Students in front of Whitin Observatory.

Professor Dick French

Dick

I met Professor Dick French as he imagined a renewed and revived observatory. He was its true champion and spearheaded an effort not only to stabilize and preserve, but also to expand the building, making a bold gesture toward other disciplines and the future.

Dick is the kind of fellow who’d take a voyage on an historic whaling ship just “to make a small connection with the feeling of relying on our own observations to know where we are.” With a late 1800’s sextant in hand, he once measured the angles between sun and moon to establish the latitude and longitude of the Charles W. Morgan. He’s constantly looking towards the universe to understand his place in it.

On one of our first visits to the observatory, Dick showed us around. Every surface was covered with priceless pieces of history, memorabilia, or artifacts. Being the Director of the Observatory, it seemed, also came with the duty of being the caretaker of a small museum. Among the realia was a collection gifted by Sir William and Lady Margaret Huggins, who collected “antiquity…to trace in its development the awakening intelligence of the race.” Dick supplied us with a list of over 100 artifacts and images he’d cataloged. It included an original copy of Exercises in Astronomy by Whiting herself, Huggins’s Royal Astronomical Society seal, a collection of meteorites, Aztec sun stone, a signed portrait of Mrs. Whitin, commemoration of Annie Jump Cannon and a gentleman’s pocket sundial which could tell time “quite near enough for the days of slow movement”. For decades, Dick had protected three stained glass panels in an office drawer. He was eager to have them refurbished and displayed as part of the renovations.

As the design developed, we hunted for opportunities to integrate proper displays. The new addition afforded us a chance to reuse historic window openings as double sided cases. Some windows had been buried by a classroom in the 1960’s but those walls were stripped away to reveal the handsome stone facade and 4 perfectly sized portals.

Those weren’t the only things lost then rediscovered as we dug through the observatory's past: Out of necessity, a hallway had carved up the original photographic room. Once removed, it was revived as a small study & meeting space. In the library, a series of tall metal shelves was removed so the space could function as a seminar room once again. Books still line the room in low shelves at the perimeter, which freed up space for the original wood table and a new rug that even Mrs. Whitin would be proud of. And finally, the original entry door, long abandoned and anchored shut, is now a memorable part of the new specialty classroom. (The rug selection process involved trips to the Boston showroom where several options were selected to try in the space. I remember well the day they were delivered to the observatory and unrolled. The delegation stared at the ground for hours! An antique Ferhan was chosen for its intricate details, patina, and color.)

While the past was honored, we were also looking to the future. Dick’s vision was to welcome Earth Sciences alongside Astronomy by adding offices and a truly unique shared teaching space. The new Specialty Classroom was designed with pedagogy in mind. With sweeping views to the Arboretum and no clear “front of the room”, it supports small group work and various modes of instruction. “I think it makes for more engaged learning. You can’t really turn yourself off when you’re in that setting,” Associate Professor of Geosciences Dan Brabander noted.

The great success of the revitalization is that it doesn’t stop there. It’s now a feature on the admissions tour, a venue for creative writing classes, and home to the college’s Edible Ecosystem Garden. It even hosted a training program “to promote inclusion by helping faculty to redesign learning spaces and experiences to engage and support all students”.

A group of volunteers at the College’s Edible Ecosystem Garden on Observatory Hill.

In 1876, Professor Sarah Francis Whiting was hired to establish the Physics and Astronomy Departments at Wellesley College.

Sarah

In 1876, Professor Sarah Francis Whiting was hired to establish the Physics and Astronomy Departments at Wellesley College. “At that time there were few options for women to pursue higher education in the US, [so the institution was created] to provide women students and faculty with the same opportunities available to men.” It was a worthy and pioneering “educational experiment”. Whiting undertook two years of training to prepare for the position, which included being the first women to attend Edward Pickering’s lectures at MIT. His hands-on methodology and laboratory instruction greatly influenced Whiting’s curriculum.

I was thrilled to discover Whiting’s achievements stunningly illustrated in a recent Physics Today piece. Professors Cameron and Musacchio provide important context:

Unfortunately, as women working in what was then very much a man’s field, Whiting and other female scientists had to deal with considerable prejudice and limited opportunities. Near the end of her career, she reflected on “the somewhat nerve-wearing experience of constantly being in places where a woman was not expected to be, and doing what women did not conventionally do.”

Some scientists took an enlightened approach to the presence of women in their ranks. In London, Whiting met Lord Kelvin; in a 1924 article for Science, she recalled being impressed when he was “neither surprised nor alarmed” by her gender.

But others were concerned about what might happen to their comfortable worlds if more women entered their fields. When Whiting met William Crookes in 1888, he reportedly mused, “What would become of the buttons and the breakfasts if all the ladies should know so much about spectroscopes?”

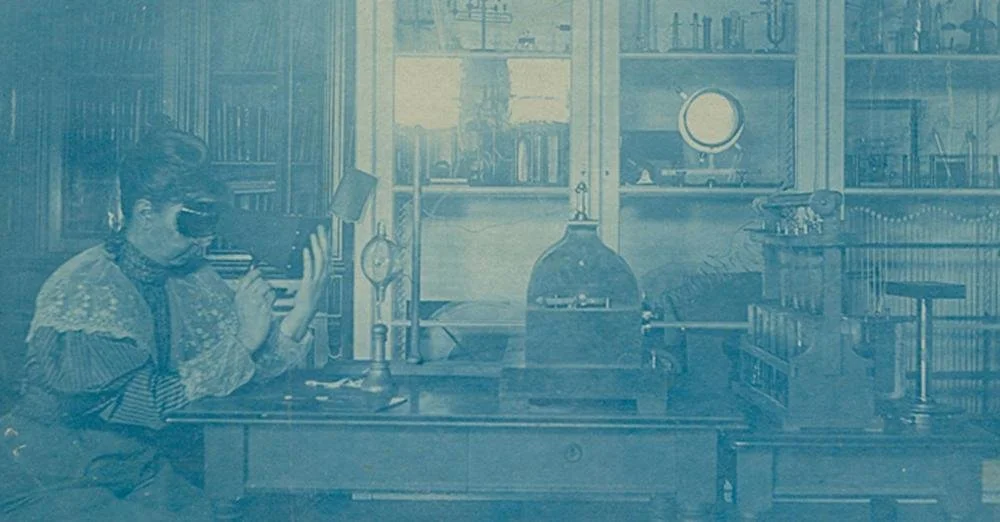

Having established the Physics Department and equipped it with a laboratory and instruments, Whiting was the first woman (and likely first person in an undergraduate laboratory) to replicate Wilhelm Röntgen’s discovery of x-rays in 1896. She worked with students by her side to produce a series of glass plate exposures. The originals did not survive, but photographs of them were recently found in a mislabeled box as part of a cataloging effort necessitated by an impending building demolition. I was struck by the visual of the notably feminine items the team chose to x-ray: various pieces of delicate jewelry, including a heart pendant and a small key. What an unmistakable thumbprint in science history!

The two Wellesley professors who found the images thankfully understood the importance of sharing them with the world, so that we all may appreciate the trail blazers before us. They wrote, “The x-ray experiments were only one instance in which Whiting drew on her keen engagement with contemporary scientific advances to offer her students an experience available to few undergraduates at the time, and to almost no women. Throughout her long career, Whiting introduced thousands of women to physics and astronomy….”

As for her establishing the Astronomy Department, Whiting orchestrated the purchase of the Fitz/Clark 12-inch telescope, “considered the finest glass in the vicinity”, and the creation of a fine observatory to house it. With a generous gift from trustee Sarah E. Whitin (often cited by her husband’s name only as “Mrs. John C. Whitin” in many referenced/formal texts), “the new Observatory began to rise on one of Wellesley’s hills.” Mrs. Whitin stipulated the white marble, for white was symbolic of both their contributions (as well as the original owner of the telescope, Mr. White). It is fitting that the exterior literally reflects their legacy today.

Such specialized use makes for a specialized building. The original ropes and pulleys used to turn the 23 foot diameter dome are still in place and operational, although it was retrofitted with a motor for more precise placement and automated movement in the mid-1950’s. Shortly after installation, the builder estimated that the dome’s weight was 15,100 pounds! A set of wooden steps on castors provide the height needed to reach the eyepiece. I’ll never forget the clear night my son and I looked at Saturn together through the antique refractor. Its silhouette glowed white against the black night and its rings were unmistakable. The stone course beneath the dome carries this motto: “Night unto night showeth knowledge.” The building was doubled in size just after five years to include a second telescope: a 6” refractor, also by Clark, its presence is obvious from the more modest dome atop.

While Whitin Observatory is technically robust, it is also elegantly comfortable and even cozy. In a 1915 journal it was remarked, “The main laboratory is a large, many windowed room. The generous fire-place with its buff brick chimney piece and blue Warsaw blue-stone shelf, the oak bookcase and richly colored Indian rug give it the air of a luxurious living room rather than a students’ work-room.”

The observatory remains as the link from past to future and the thread that ties Professor Sarah F. Whiting to tomorrow’s female scientists and leaders. However, a century of service showed its signs. Many handsome details were overwhelmed or buried and by 2009, the place required attention.

Whiting’s x-ray photograph of objects in a leather pouch.

Artifacts on display in a restored window opening.

Library complete with original fireplace and new display cases.

Professor Kim McLeod

Kim

Professor Kim McLeod carries on the vision and in 2019, she picked up where Professor French left off as Director of the Observatory. She spearheaded the replacement of the 24-inch Sawyer Reflecting telescope with the new CDK700 (by PlaneWave Instruments). This new equipment supports advanced research projects, including the exploration of exoplanets as part of a NASA collaboration. It allows students first hand experiences, collaborating with professors on real world problems, much in keeping with Sarah Whiting's program.

Kim is the perfect professor to carry on Whiting’s legacy. She's the type of person who will do handstands just to encourage her students to take a new perspective on the world. She's a gymnast turned astrophysicist, and the ultimate cheerleader for math and sciences. She thinks about astronomy as the gateway to physics for those studying in the arts and humanities that don't consider themselves interested or capable. She's the ultimate advocate and it shows in her work and care for this place.

Pac Man Nebula, Savannah Cary ‘22

Savannah

Kim introduced me to some of her students. I had the pleasure of speaking to Hannah Stickler and Savannah Cary, both seniors on track to graduate in May of 2022. They were involved in setting up the new telescope equipment over a summer and are intimately involved in the Planewave Project. They told me about their time at the observatory and I was very touched to hear many of the details meaningful to them were some that Sarah Whiting had made sure were included. And we were careful to maintain them.

There's a sense of community, a sense of home in places like the small library with a fireplace, and warm wood tables and big soft chairs that make the observatory feel like a safe place, a comfortable place for students to come together. The seniors pointed to their early time in the building, when they were “still finding their community”. They were able to sit next to upperclassmen, work on problem sets or just compare notes about life on campus or life in general. They had access to the kitchenette, which may seem like a small thing, but to them making tea at midnight with their friends was an important social bond. Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, students don't have the same access within the building anymore. Protocols are evolving all the time.

Savannah understood that a place to gather is important, especially after being separated from her peers for some time. Having a place to come together means the world and I believe the observatory will continue to do that in the future: to be a place to explore, to study, to meet and to see things you'd never seen before.

I feel privileged to be a part of the introduction of new disciplines into Whitin Observatory. To me, it's poetic to combine the exploration of the ground and the exploration of the sky. My hope is the colocation helps students appreciate and understand one another's work, from a geosciences student team project exploring herbicides in tampons to Savannah’s photographs of nebulae.

Savannah described to me the process of capturing an image on the new telescope. It's something that takes many hours of observation, she explains. Of course, the Earth is constantly turning, and the view of the stars is constantly changing. So the scope itself has to track with the changing view. The telescope doesn't take color photography, so different lenses are applied to filter the light. Savannah takes exposures in red, blue and green and combines them to get a color image. Individually they look black and white. The space observed is so large that she also captures different quadrants and then stitches them together to render an entire nebula. I love comparing the image that Savannah created with the X-rays that Sarah Whiting took. They speak to seeing the world in a way that others haven't before and the love of discovering and sharing with others.

In 1900, Professor of Mathematics Ellen Hayes wrote of the newly opened Whitin Observatory, “One’s imagination is taxed in trying to picture the long procession of young women whose lives are going to be made richer and nobler by this far-reaching benefaction...We shall one by one close our eyes on the stars, but the beautiful observatory will remain. Those who come after us will take up the work, watch the skies, and go on with the records in our stead.”

There's something beautiful and artful in the rigorous scientific work being done at the observatory and the work goes on.

Unfortunately, as women working in what was then very much a man’s field, Whiting and other female scientists had to deal with considerable prejudice and limited opportunities. Near the end of her career, she reflected on “the somewhat nerve-wearing experience of constantly being in places where a woman was not expected to be, and doing what women did not conventionally do.”

Students and the new CDK700 telescope.